The Last Days of the Carlton Hotel...

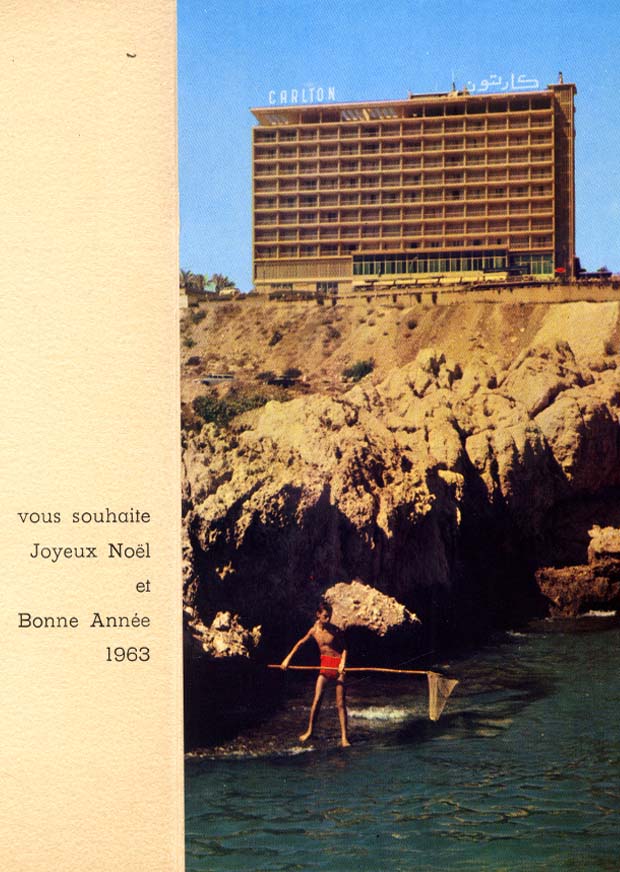

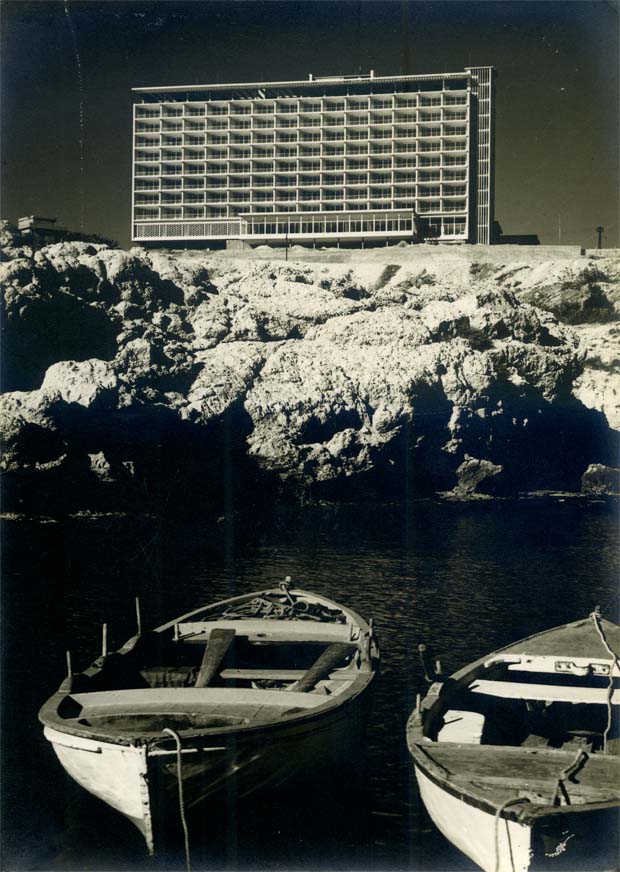

"On the large avenue leading from the airport to the city along the seashore, the Carlton spreads its facade along the corniche which surrounds the new residential parts of Beirut. The Carlton was constructed in such a manner that all rooms face the sea giving equal opportunity to enjoy the splendid scenery.” - Unknown

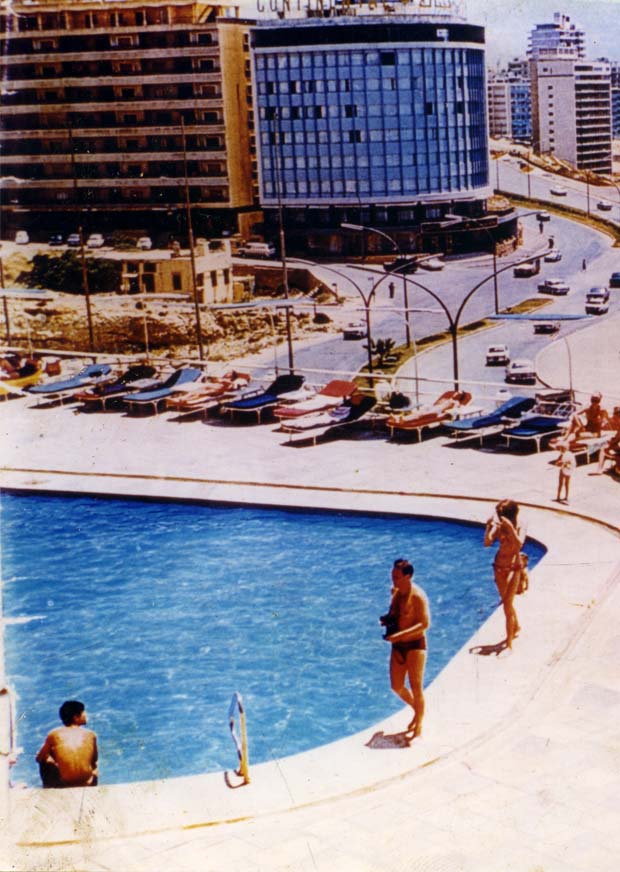

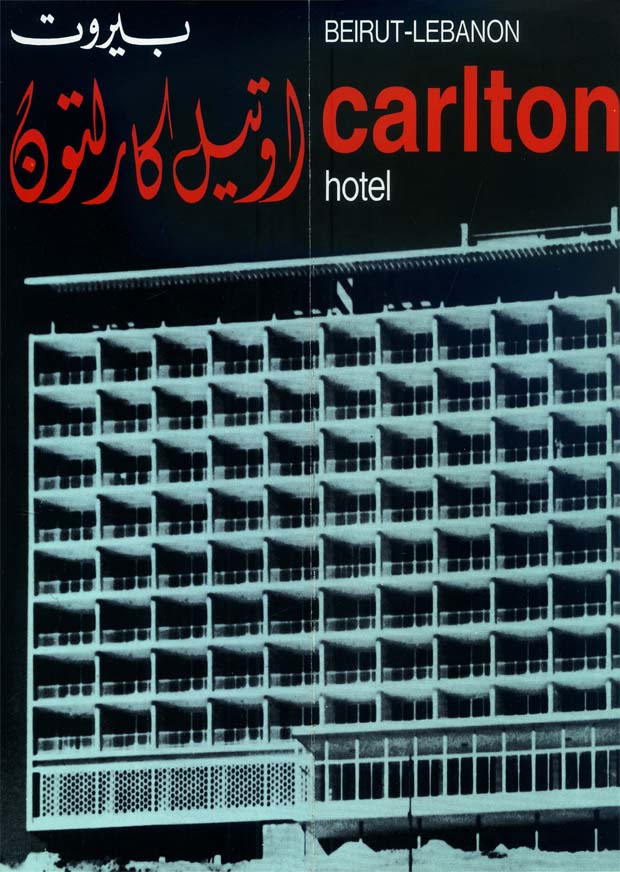

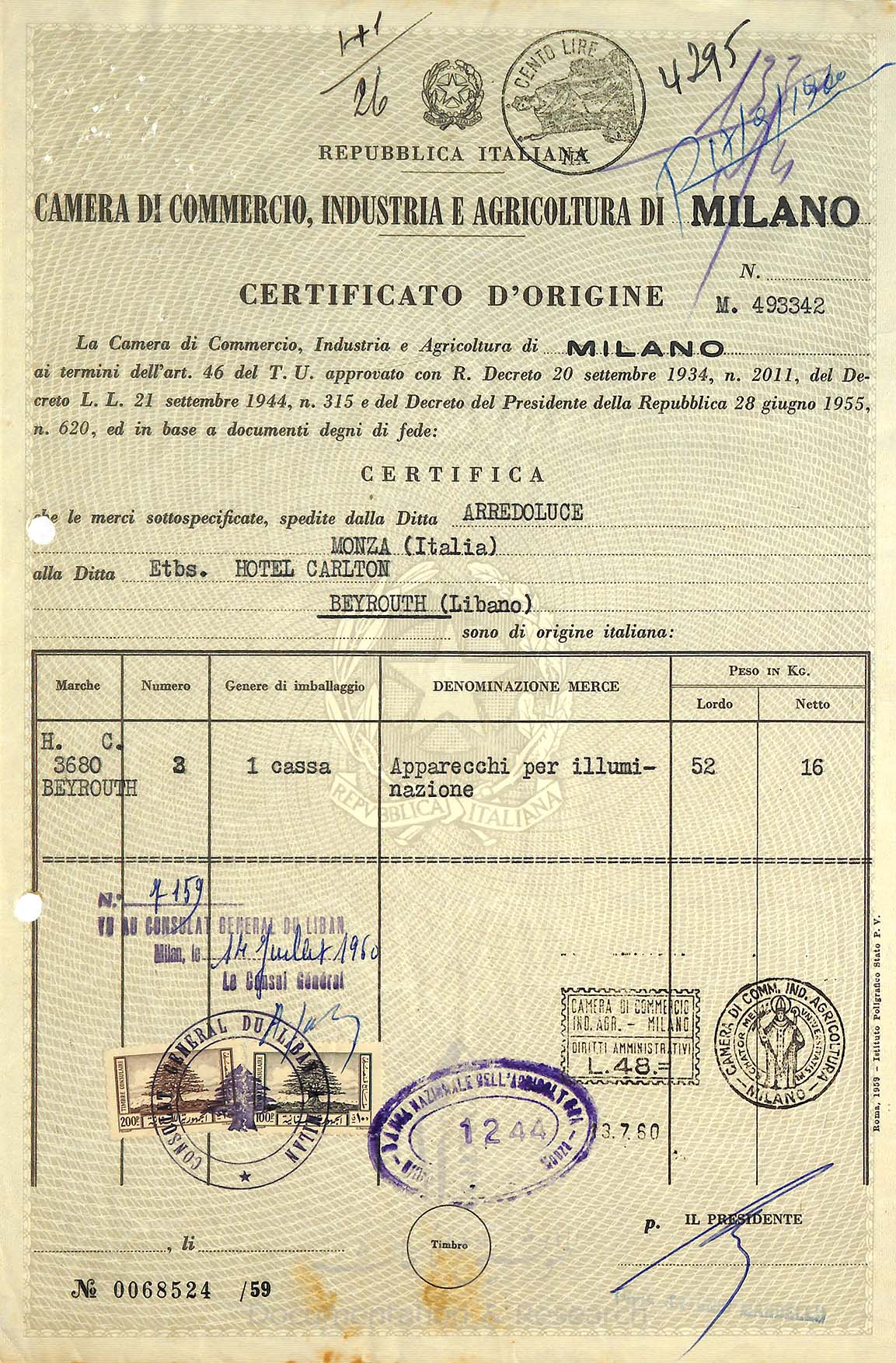

The Carlton Hotel was designed by the modernist Polish architect Karol Schayer in 1957 and built along the Corniche in Beirut, Lebanon. Decorated by Michel Harmouche, the lobby’s dominant color was pink with fine furnishings imported from Europe. Its distinctive bean-shaped swimming pool and the rooms’ splendid views of the Mediterranean set it apart as a luxury hotel. The hotel’s superior French cuisine and candlelit dining room especially was a point of pride.

The hotel opened its doors in February 1960 to the glittering cultural elite of the region, wealthy tourists, and international diplomats. Throughout the 1975-1990 civil war, the hotel’s guests included journalists and political figures, but it eventually succumbed to a compromised tourism industry and poor local economy, and could not recover after the war. In 2008, the Carlton Hotel was sold to real estate developers to be destroyed and a three-tower residential complex to be built in its stead under the name “Carlton Residence.”

The Carlton Hotel Collection

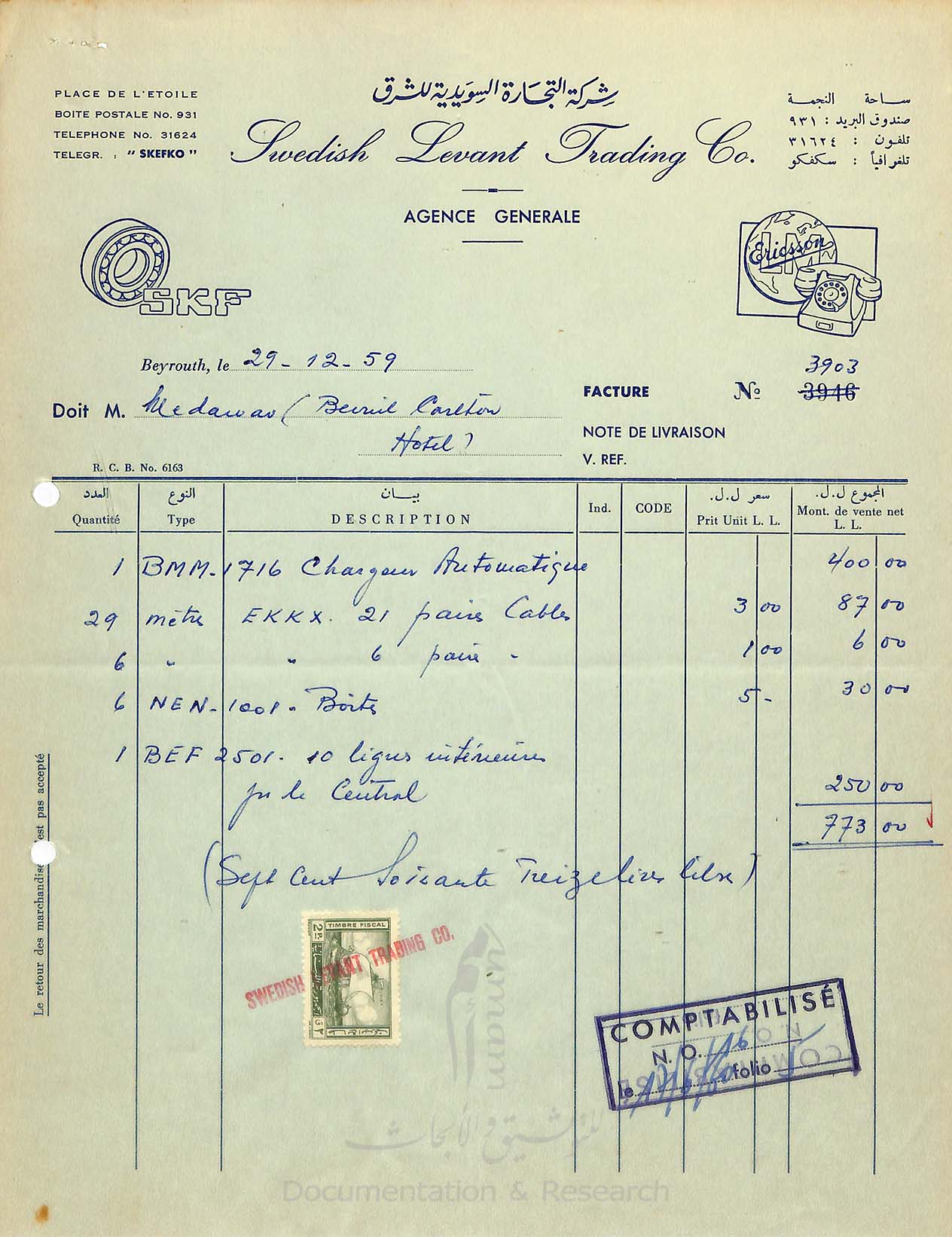

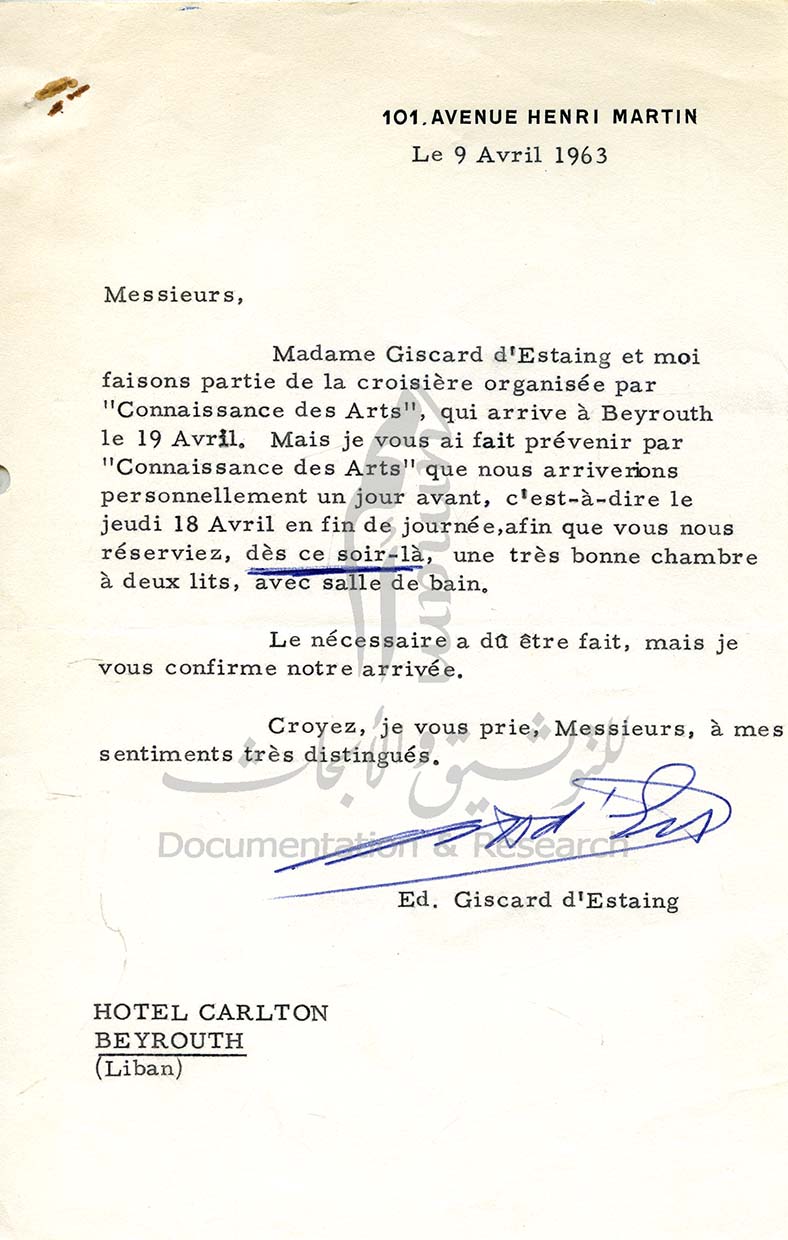

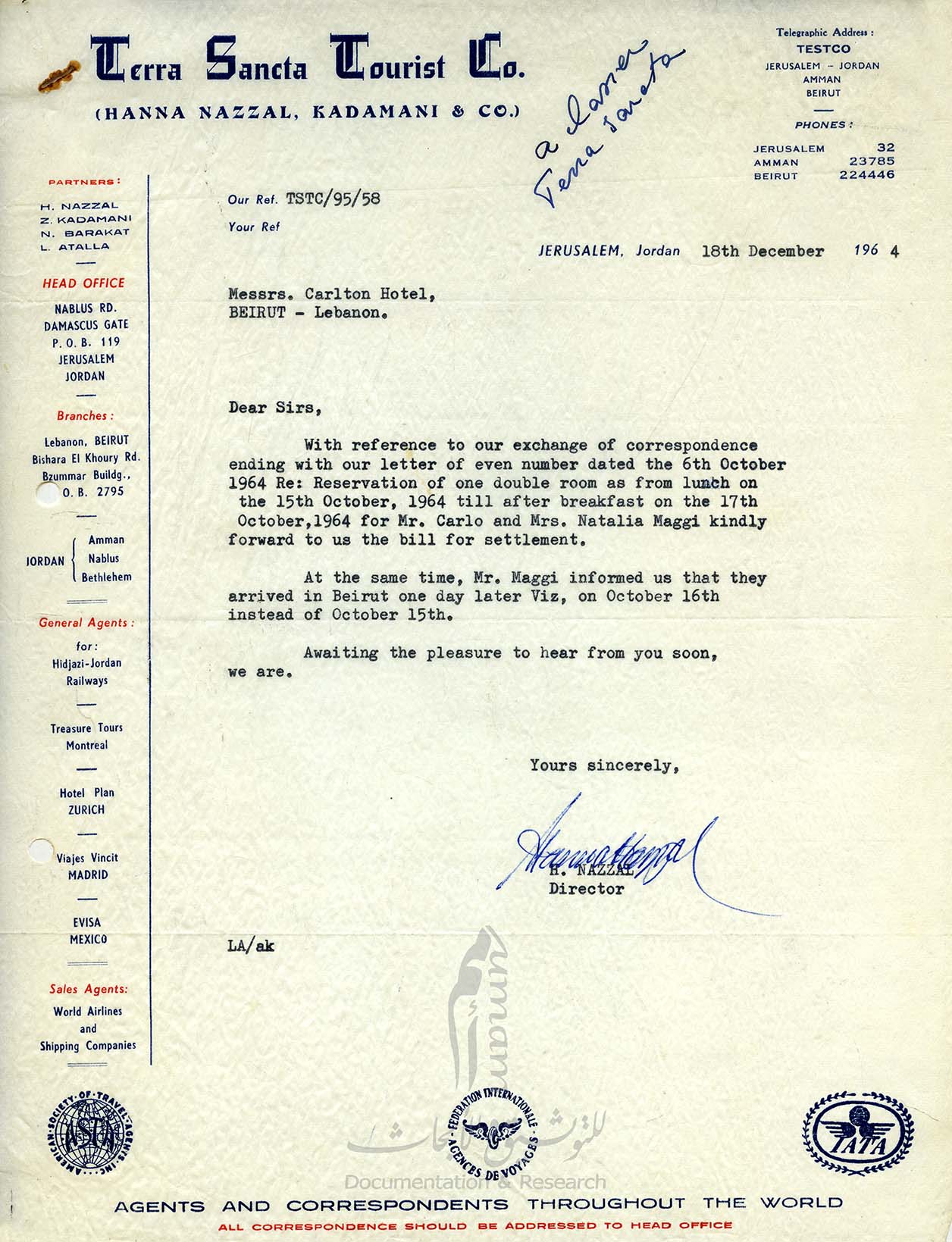

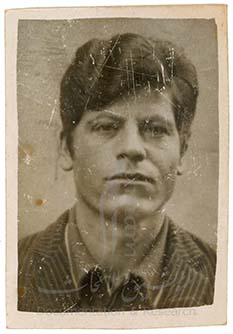

Thanks to a serendipitous coincidence shortly before the building’s demolition, UMAM D&R was able to retrieve several tons of documents left in the building before they were destroyed or lost to oblivion. The collection comprises 574 original folders containing memoranda about events, parties, and conferences; accounting data; suppliers’ bills; legal documentation; personal correspondence; newspaper clippings; information about employees and salaries; and even restaurant bills. It also contains 400 bound ledgers detailing guest bills, occupancy, and operations logs. Furthermore, the collection includes miscellaneous items such as business cards, swimming pool tickets, restaurant and special occasions menus, employee identity cards, and architectural drawings. The materials date from 1955 to 2001: while the Carlton Hotel opened for business in February 1960, the archive includes a number of materials that predate its opening and focus on, for instance, the construction of the building. Also included in the collection are numerous records that relate to Hotel Regent, another hotel that was located in Beirut’s Martyrs' Square and was the forerunner of the Carlton Hotel, as both hotels were owned by the Medawar family.

Not only do these archival holdings, now under the safekeeping of UMAM D&R, help to document the Carlton's development over time, they also narrate aspects of day-to-day life within the prestigious hotel. The collection allows viewers the opportunity to experience a wide array of episodes that defined life in the Carlton Hotel, including the Communist Congress that took place on its premises in 1972, complaints by desperate guests about trousers that had shrunk while being laundered, inquiries from a woman wanting to know how long her husband had been a guest at the hotel, the destruction of the tenth floor due to a fire, and the impact of the takeover of West Beirut in February 1984.

The Carlton Hotel collection provides a rich compilation of stories by and about guests, deputies, celebrities, journalists, cooks, receptionists, and civil war militiamen, that coupled with insights into the business itself, helps reanimate life as it was during the late 20th century within this microcosm of Beirut. Importantly, it gives a tangible sense of the events that influenced the Carlton Hotel as it would forever be changed by the civil war that came to life just 15 years after it opened for business. The story of the Carlton Hotel is one that closely mirrors that of Beirut, and Lebanon, itself.

The Golden Age of the Carlton Hotel (1960 – mid-1970)

The collection offers valuable insights into the development of the Carlton Hotel during the 1960s. That growth, due particularly to the surge of tourism in the region, becomes evident when perusing the sheer volume of correspondence the hotel received from travel agencies and automobile clubs throughout Europe, most of which expressed a desire to expand their presence in the Middle East. In the mid-1960s, the number of European tourists surged in the Middle East. Among other destinations, they visited Lebanese landmarks, journeyed to Damascus, and eventually visited the “Holy Land.” A number of letters in the collection request information about the travel time from Beirut to Jerusalem by automobile. Some travel agencies, such as American Travel Service, coordinated visits to Lebanon by groups of 100 – 200 tourists. During the Carlton's heydays, extended stays at the hotel (a month or more), were common.

The Carlton quickly became renowned as a leading Beirut luxury hotel, placing it in competition with the famous hotels of Martyrs' Square. Guests of the Carlton came for its relaxing atmosphere, close proximity to the sea, and the exemplary quality of the services it provided. At the time, advertisements for the Carlton Hotel described it as nothing short of an oasis: “All rooms are facing the sea, have a private terrace, individually controlled air conditioning, telephone, bath, radio, etc. Use of the freshwater swimming pool is available free of charge to all our customers. We are also renowned as a hotel with the finest French cuisine in town.”

Although the Carlton Hotel enjoyed a stellar reputation among wealthy European visitors, it did not rely solely on word-of-mouth advertising. Catalogs and guides published by travel agencies and clubs—included in the collection—remained the most important means of promoting the Carlton. Each year, travel agencies worldwide requested current price lists and pictures of the hotel.

The give-and-take nature of doing business also becomes evident when reviewing the range of correspondence. For instance, the hotel agreed to grant discounts to all guests whose travel had been coordinated by one of the tourist businesses with which it was affiliated. More precisely, it appears that Antoine and Nicolas Medawar had little leeway where such agreements were concerned, as travel agencies, embassies, airlines and even individuals requested similar discounts. Owing to the fierce competition that existed at the time between Beirut's luxury hotels, managers at the Carlton had little choice but to acquiesce in order to preserve the hotel’s high reputation.

With respect to competition, Beirut's Phoenicia Hotel was among the Carlton's strongest competitors. Built in 1961, the Phoenicia expanded in 1966 with the addition of a 22-floor building. In November 1969, the Phoenicia issued a press release that hotel guests had access to a “teleprinter,” which they could use to stay abreast of the latest news. The following day, managers at the Carlton received a letter from Reuters offering them a better teleprinter. A prospectus published by Thomas Cook & Son Ltd. identified the Carlton as being in the "First" category of hotels in Beirut. On August 23, 1968, Antoine Medawar, one of the Carlton Hotel's managers, argued that it should have been included in the “LUX” category because of its facilities: « Cette classification nous cause un préjudice très grand surtout que COOK est une agence sérieuse et écoutée dans le monde entier. Nous avons consenti pour vous des prix inférieurs à nos tarifs pour encourager le tourisme en cette période de crise, il ne faut pas que le prestige de l’Hôtel en souffre. »

As is evident from the above and by many other examples of correspondence, the general situation in the Middle East following the 1967 Arab-Israeli War had a negative effect on regional tourism. To ensure the Carlton remained an attractive choice, its managers were forced to reduce prices. Notably, changes to the security conditions in the Middle East were not solely responsible for the economic difficulties being faced at the time by Lebanese hotel operators. On January 7, 1970, the Lebanese Hotel Owners Association sent a letter of protest to the Ministry of Tourism about the excessive number of hotels in Beirut. The abundance of competing businesses reportedly caused economic hardship among hotel owners, a situation they described as eventually compelling them to fire their employees.

Fortunately, the tourism industry seemed to be on a rebound in the early 1970s. The increased demand for tours to Lebanon prompted the Carlton's managers to consider expanding the hotel. As envisioned, the project was to have included construction of a 22-floor annex, the addition of 10 floors to the existing building and a new wing on the north side of the hotel. All told, the project was to have provided 383 more guest rooms. Soon enough, however, that tide would change. The events of April 13, 1975—the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War—would ultimately destroy the Carlton's ambitious dreams of expansion. By extension, the war would wreak unspeakable damage on those of Lebanon itself…

Coping with the War

The Lebanese Civil War had a tremendously adverse effect on the fortunes the Medawar brothers. For instance, the first two years of the war resulted in the demise of the Hotel Regent and severely reduced room occupancy rates at the Carlton. Since the Carlton Hotel was “practically closed during that time,” its managers suspended all advertising in tourist brochures.

In 1981, Antoine and Nicolas Medawar requested that Banque Libano-Française extend the period of their loan, explaining that they were unable to pay the bonds due to the “current situation.” That same year, the brothers announced that security conditions in Beirut had impeded construction of the new building. Although the initial period of the conflict indeed placed the Medawar brothers in a serious predicament, the heavy fighting that took place in West Beirut from 1982 onward had a much more profound impact on the Carlton Hotel. The war caused material damage, decreased occupancy rates even further, and eventually forced a six-month closure of the hotel in 1984.

On September 6, 1984, violent clashes broke out in West Beirut between militia groups headed by the Amal Movement and the Lebanese Army. That fighting sparked a fire on the tenth floor of the Carlton, which caused severe damage to the hotel. The army maintained a short-lived presence in West Beirut before being impelled to withdraw from the area because of the intense fighting, at which point the Carlton Hotel was soon surrounded by armed groups vying for control of the area. To remain in business, the Carlton was eventually forced to submit to the "goodwill" of those groups.

From late 1984 onward, the collection contains evidence of many “required” financial donations from the Carlton Hotel’s managers to those militia groups. Beginning in October 1984, numerous receipts mention the purchase of official newspapers published by the Amal Movement and the Progressive Socialist Party, with similar expenses posted during the next two years as well. A Hezbollah publication is also mentioned in correspondence from August 1985. Many entries in the hotel's accounting ledgers also indicate donations having been made to these organizations.

Because of the intense fighting that was taking place in the city, and sometimes around the Carlton itself, the number of hotel guests declined precipitously. Although room occupancy rates reached 80% in the summer of 1977, they plunged to 30% in 1983 and 1985, and they were near zero in 1984. The Medawar brothers had no choice but to seek additional financial resources in order to withstand the crisis, and it was ultimately suggested that they open a casino in the hotel's basement. In a letter written February 19, 1985, Chef Maurice Marchais conveys his belief that a casino would help the Carlton overcome its difficulties. Although an invitation card in the collection suggests that the casino opened on August 24, 1985, brief articles in An-Nahar and As-Safir indicate that event was postponed due to security reasons. Nevertheless, the new "Midway Casino" finally opened. Between 1985 and 1986, it hosted a number of private events, each of which was attended by 40 – 60 guests.

Clearly, the Medawar brothers were under duress because of the Civil War, and elements included in the collection suggest that the actions they took in response to that situation were simply efforts made to save what remained of their beloved Carlton Hotel.