Our Collections

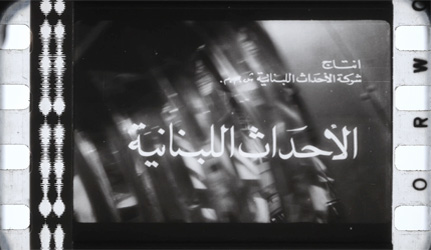

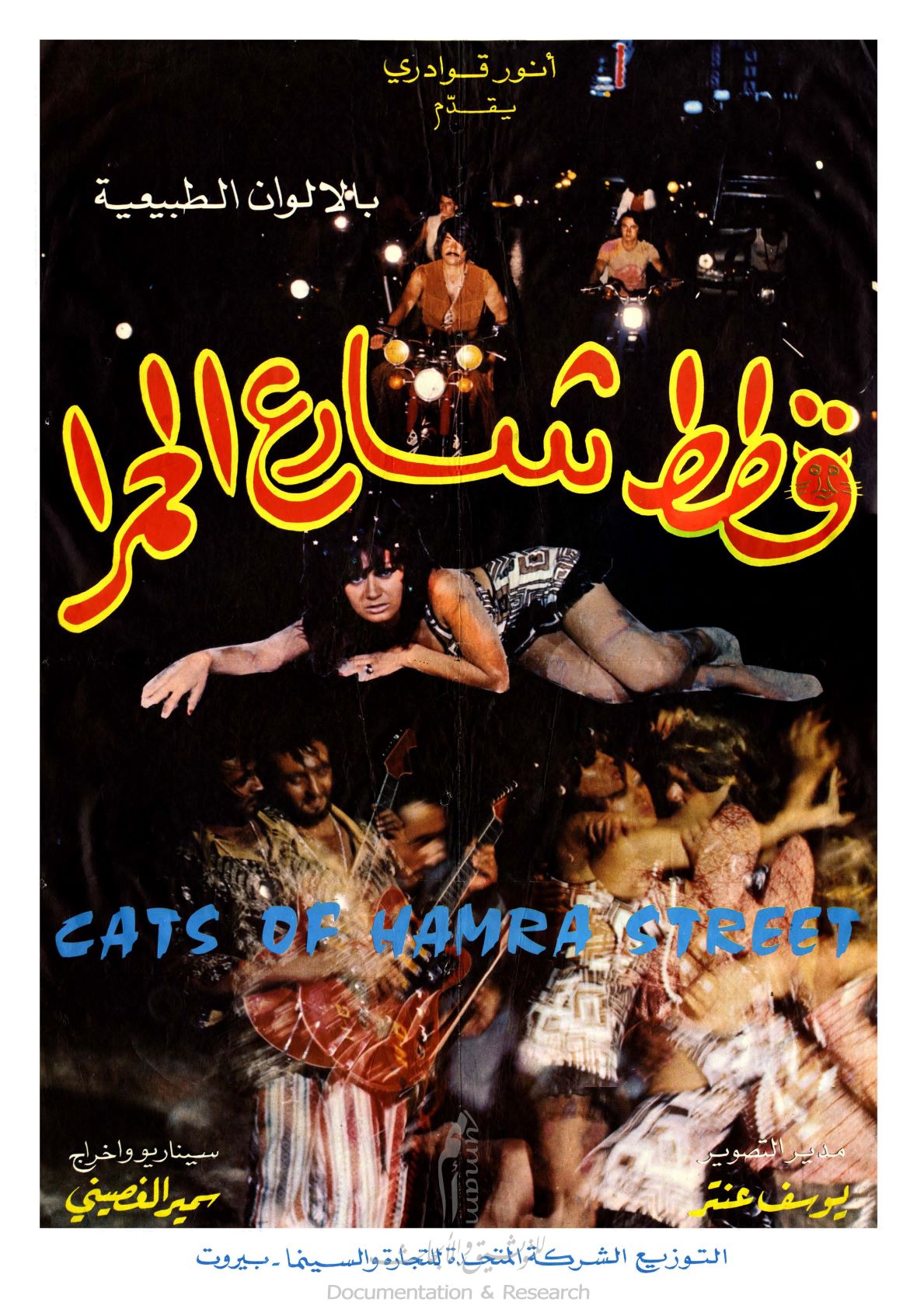

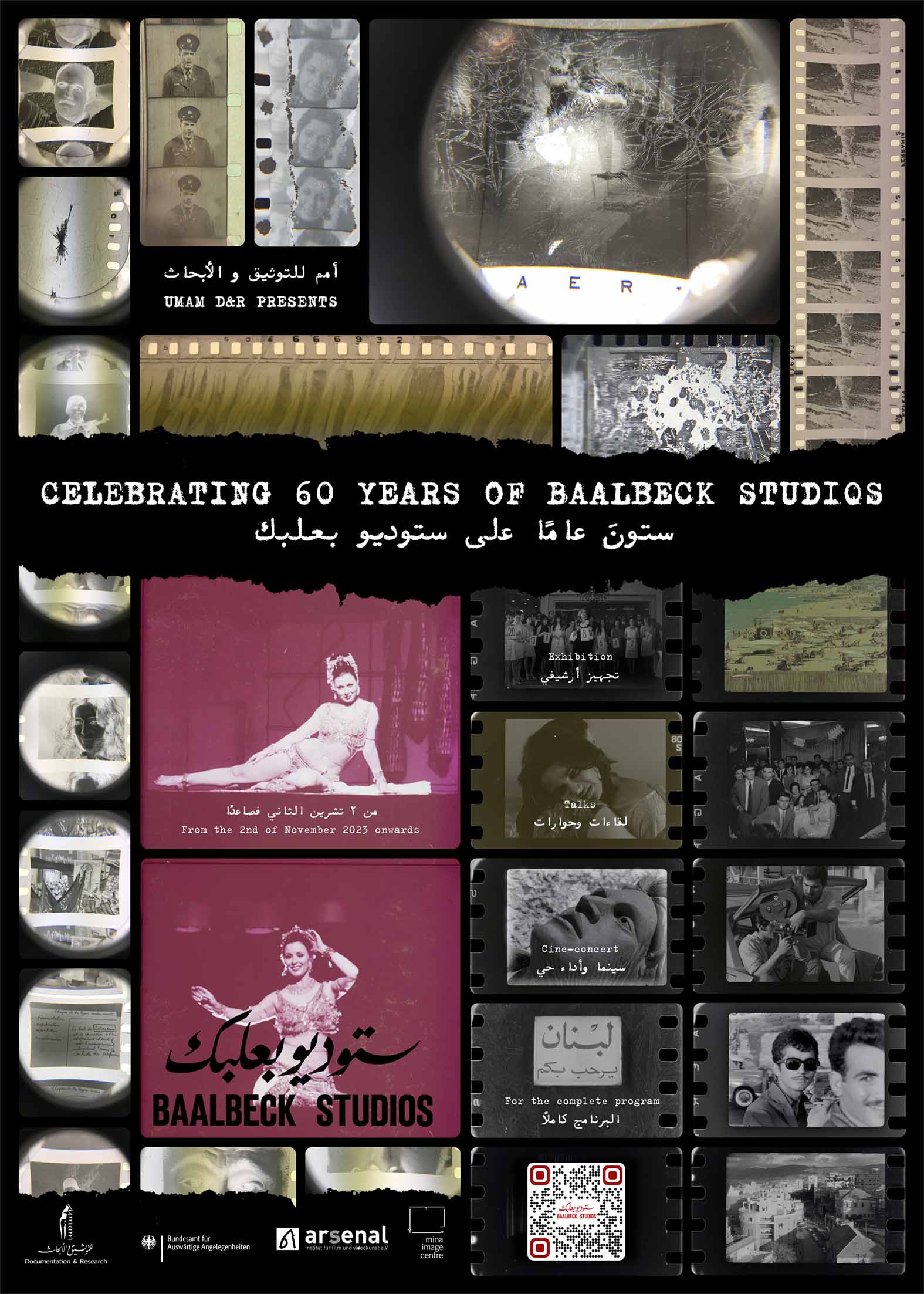

Baalbeck Studios

Baalbeck Studios, founded in Lebanon in 1962, was one the of the leading film studios and the preeminent recording studio in the region to come "shoot in sunny Lebanon." In 2010, UMAM D&R salvaged written and audio-visual archives from the offices slated for demolition.

Our Collections

The Carlton Hotel

The Carlton Hotel opened its doors in February 1960 to the glittering cultural elite of the region, wealthy tourists, and international diplomats. In 2008, UMAM D&R salvaged archives before the building was destroyed and became the residential complex called “Carlton Residence.”